Personalisation, programmatic, gen AI blow brand carbon budgets – but some agencies now mapping ads to renewable power peaks, slashing emissions

Marketing's adtech and personalisation obsession is blowing out brands' carbon emissions while accelerating generative AI use risks 10x increases. Relying on the renewable energy promises of SaaS vendors and hyperscalers like Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Google who host them or provide their LLMs won't solve the problem – because their own emissions are running out of control for precisely the same reason. But renewable generation means there is a new meaning to 'right ad, right place, right time' – and some agencies are starting to match digital ad buys to within-day periods of high solar and wind power.

What you need to know:

- With a new regulatory regime that will require carbon emission accounting comparable to financial accounting, Australia's marketers may soon find themselves being asked some very uncomfortable questions.

- That's because some core technology infrastructure they have come to rely on – such as the programmatic supply chain – is already a bloated energy hog and generative AI could further blow out emissions by an order of magnitude.

- In some industries, the AI-powered personalisation of product and the marketing underpinning it will add a new layer of CO2 into the mix.

- While SaaS vendors and hyperscale digital vendors who host them or who host their own LLMs claim they use 100 per cent renewable energy, the truth is they usually don't – it's an accounting trick. In fact, most are pumping more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than ever before.

- But some agencies are starting to plan digital ad buys mapped to high levels of wind and solar power in real-time, dramatically slashing their carbon emissions.

- We're not going to meet our energy goals anyway, so bet on AI solving the problem, says former Google CEO and Chairman, Eric Schmidt.

By not marketing to the wrong markets, in the wrong places, and by not blanketing the advertising out there but by being much more targeted they've been able to generate savings.

Marketers, through their obsession with personalisation, reliance on programmatic advertising, and pole position as generative AI first movers, are high-octane contributors to their organisation's carbon emissions.

The problem is compounded in Australia by a power grid that remains highly reliant on coal.

According to Hearts & Science's chief digital and innovation officer, Ashley Wong, last year "7.2 million tons of carbon were generated from advertising and marketing, specifically from digital advertising".

And it's getting worse.

"We are personalising and making things more addressable. If you think about streaming video we've gone from a world where someone turns on a TV and that signal's being transmitted once, but now we're in a world where everyone's on BVOD or on YouTube, think of all the different servers that are involved in delivering that one to one content."

He told Mi3, "It's not even personalised in the way that people normally think about personalisation, that adds to an immense use of power that ultimately, depending on where that power comes from, generates carbon. Australia is very different from a lot of markets around the world. Nuclear, whether or not you like it, technically doesn't emit carbon. But Australia, because 70 per cent of our power is generated from non-renewables ... it means that our grid is largely dirtier than a lot of these other grids. That makes a big difference in the Australian market."

Getting the right message to the right person at the right moment carries an additional carbon burden.

"It's a world where we've gone from one-to-many, to largely in more digital formats [where it is] one-to-one. That means that each ad is individually delivered to each person. Whether or not that's personalised, it's addressable, there is a lot more power being used to deliver these messages. Unlike the old world of linear TV or print, where things are produced once and shipped."

Now, says Wong, every time someone wants to view an ad or a piece of content, servers fire up and the energy meter ticks over.

"I think that is going to be the biggest challenge as we become more and more digital, and [more] one-to-one, and on-demand. It's these things that are going to drive the increase of carbon emissions," he says, "along with generative AI."

Product personalisation

In some sectors, product personalisation by brands also drives unsustainable energy outcomes.

Fast fashion is a good example, as Chinese ecommerce giant Shein is now finding.

Shein, whose 2023 revenue was reportedly $US32.5bn has set its sights on almost doubling that by 2025. According to Grist, an independent not-for-profit media business that specialises in climate issues, Shein's growth is powered by AI which it uses to rapidly churn out affordable, on-trend clothing. Its personalisation algorithms allow it to produce tailored products in very small batches – as few as a few hundred units.

And therein lies the problem. The report cites critics of the business claiming its, "lightning-fast manufacturing practices and online-only business model are inherently emissions-heavy — and that the use of AI software to catalyse these operations could be cranking up its emissions."

The evidence can be found in Shein's own sustainability report where it just reported a staggering increase in carbon emissions rising from 9.17 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent in 2022 to 16.68 million metric tons in 2023 – an 82 per cent increase in 12 months.

The company attributes the surge in emissions primarily to an expansion in operations, which included the introduction of Shein Marketplace, a new platform that allows independent sellers to offer their products through Shein's extensive logistics network. This diversification has led to increased transportation and distribution emissions, which accounted for the majority of the rise in total emissions.

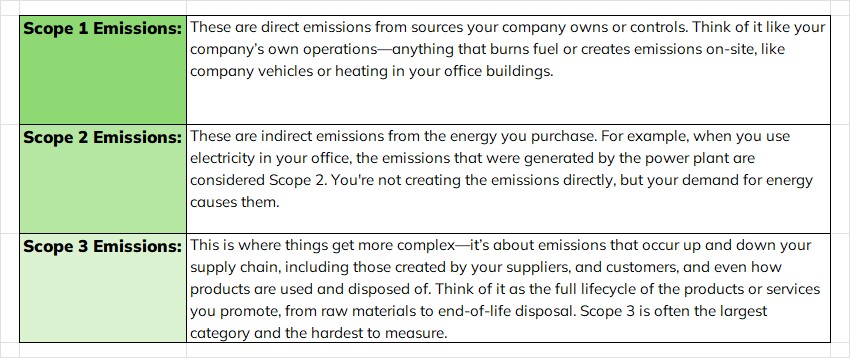

Specifically, Scope 3 emissions, which arise from supply chain activities and are outside Shein's direct control, saw a significant increase, illustrating the challenges of managing emissions in a rapidly growing e-commerce business.

It's also a case study of how a brand's sustainability practices can rapidly attract the kind of angry headlines that sustainability-conscious consumers are unlikely to ignore.

"Shein is officially the biggest polluter in fast fashion. AI is making things worse," according to Grist. And it was not alone in its assessment or its reporting. "Shein emits more pollution than the country of Paraguay," screamed Fashionista. "Shein: Fashion's biggest polluter in four charts," The Business of Fashion intoned. These follow Reuter's headline a month ago which focused on its suppliers' child labour practices which in fairness Shein disclosed in its sustainability report.

Shein's scale makes it a dramatic case, but Australian brands should take note.

As Mi3 recently reported, large Australian organisations face mandatory climate reporting on both direct and indirect carbon emissions under new Australian legislation. Furthermore, those reports must be audited and they will be held to the same standards and rules as financial reporting – and the legislation will trickle down to medium sized firms over the next couple of years.

In almost all companies and industries, supply chain emissions, or Scope 3 emissions, make up by far the largest chunk of reportable emissions.

For marketers and sustainability chiefs, this is where emissions within their direct control start to cross over into those they cannot directly control, but are still required to measure and report upon.

That is why specialist emissions consultancy Scope 3, helmed by former AppNexus founder Brian O'Kelley, has adopted that moniker. Its mission is to map and benchmark emissions end to end and advise brands on how to reduce them, fast. (O'Kelley reckons firms that cull ad supply chains can halve digital ad emissions within 12 months.)

Marketing's share of the numbers are significant: insurer NIB estimates that 59 per cent of all group emissions were media and marketing. University of Tasmania's marketing department likewise recognised the scale of the sustainability-drag of digital marketing and has been able to cut emissions by 30 per cent. It has now been rated the best university in the world for climate action for three years running.

According to the University of Tasmania's chief sustainability officer, Corey Peterson, "We've been working with our digital communications people, and they have found significant savings working with Scope 3. By not marketing to the wrong markets, in the wrong places, and by not blanketing the advertising out there but by being much more targeted they've been able to generate savings."

The scale of the impact of adtech is demonstrated by the kinds of reductions the university was able to achieve when it tackled them head on via a campaign optimisation trial with its agency Pivotus.

As Mi3 reported in late September, that campaign, which ran from March to May this year, resulted in a 76 per cent drop in gco2pm – grams of CO2 per thousand impressions, the metric the university uses to measure advertising emissions and one being adopted universally – in one month. There was also a 30 per cent decline in total media emissions overall. The ongoing commitment to reduce emissions has seen an additional 10 per cent drop and University of Tasmania is currently performing 20 per cent below the Australian benchmark for web ads.

At an IAB event where she was presenting, Courtney Geritz, marketing director, University of Tasmania, told attendees that marketers, "... have been responsible for a bit of spray and pray here and there." She said the big decision Uni of Tasmania made was to forego clicks – a metric that remains very real in many organisations – in favour of conversions. The precedent was there: A previous campaign for acquisition reoriented away from clickthroughs had resulted in a 35 per cent increase in conversions.

Generative AI

The carbon emissions devil is found among the details. For instance, image generation is a popular and seemingly simple marketing use case. Creating a single image for a campaign in a few seconds using generative AI can actually save emissions if the alternative is a creative director sitting at a high-powered PC for hours iterating designs. But that's not really how generative AI imaging is being sold in by vendors. Instead, it's being pitched as a world where marketers can generate hundreds of variations of an image, each targeted personally to the 'unique needs of a customer'.

But that raises new sustainability questions.

"How many copies of those hundreds of images are then stored on computers all around the world?" asks Peterson. "How many are actually used in marketing campaigns?"

While NIB and the University of Tasmania can be seen as trailblazers in Australia in tracking the carbon inefficiencies of digital marketing, marketers now need to address the impact of generative AI on organisational emissions.

Research by firms like McKinsey reveals that marketing is an early driver of business use cases for generative AI.

Additionally McKinsey found that marketing (and sales) experienced the biggest increase in gen AI adoption from 2023 and that "reported adoption has more than doubled." Content support for marketing strategy and personalised marketing was the leading use cases. That gels with research from Salesforce which found that the most common use of generative AI among marketers is: basic content creation (76 per cent), writing copy (76 per cent) inspiring their creative thinking (71 per cent) analysing market data (63 per cent) and generating image assets (62 per cent).

But as Mi3 reported earlier this year, generative AI comes with a painful sustainability sting in the tail. Gen AI search, for example, can use anywhere from 10 to 25 times more energy than a comparable "traditional" Google search or image creation where a single image generated by a tool like MidJourney is the equivalent energy to recharging an iPhone from zero to full.

Brands have relied on machine learning and AI for years, but the impact of generative AI is orders of magnitude greater according to Peter van der Putten, director of the AI Lab at Pega, which provides AI-driven real-time decisioning for companies such as Commbank, NAB and ANZ.

"There's a difference between the consumption cost of generative AI versus more traditional AI – and it's a big difference.

"It's hard to get details on generative AI because a lot of the providers are quite tight-lipped about their estimates. But Meta, for instance, released a new herd of Llama models (used for generative AI), and they were quite proud to state that they could scale their model training to 16,000 GPUs."

He told Mi3, "Those are not the regular GPUs that you have on your laptop. These are H1 100 GPUs. So it means they cost over $US30,000 a piece, they have 70,000 cores and over 80 gigs of memory."

And Meta is harnessing 16,000 of them.

"I looked into our training environment, particularly the training of our online learning models (for traditional AI), and for the vast majority of our customers, 90 per cent of our customers, we only have one Amazon node with four virtual CPUs running to train those models."

"That's 90 per cent and the other 5 per cent have two nodes, one or two nodes of very simple AWS CPU versus 16,000 other GPUs. It's orders of magnitude, so there is a very big difference between those two types of AI."

Our indirect emissions (Scope 3) increased by 30.9 per cent. In aggregate, across all Scopes 1–3, Microsoft’s emissions are up 29.1 per cent from the 2020 baseline.

Buyer beware

If Moore's Law has taught us anything it is that generating efficiencies over time is something at which the IT industry excels. However, when it comes to cutting Scope 3 carbon emissions, if brands are relying on the renewable energy promises of digital giants like Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Google, that could prove to be a losing strategy. Generative AI has upended all of their plans, and now their real-world emissions are spiralling.

Marketing and creative software vendor Adobe says more than 9 billion images have been produced on Adobe Firefly since it was created. With generative AI images requiring as much energy as it takes to recharge an iPhone from zero to full according to academic studies, that figure equates to more than half a million tonnes of carbon emissions pumped into the atmosphere in less than two years. When asked about the environmental impact, executives fell back on the argument that its cloud provider – Microsoft's Azure – uses 100 per cent renewable energy.

Azure does not in fact use 100 per cent renewable energy, and it never has.

It's a sleight of hand that all the hyperscalers like Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta employ, and it involves the purchase of carbon offsets and renewable energy credits (REC). It's the same pea and thimble trick, for instance, that allows Amazon to claim that Australian companies that lift and shift their on-premise AI workload onto the Amazon Web Services cloud can bank carbon emission reductions of 99 per cent. It's technically true under current rules. But it is a carbon-accounting fudge. Drill beneath the top line, and the reality is cloaked in nuance.

94 per cent of the benefit comes just by lifting and shifting the exact configuration into the AWS cloud and taking advantage of everything from the concrete and steel used in the data centre's construction through to the impact of virtualisation, a technology that allows a single physical computer to act like multiple virtual machines that can run different applications or operating systems, and share resources. The 5 per cent balance comes from some Amazon optimisations.

But the real kicker is the detail: What makes up the 94 percent? First, the good news: 24 percent comes from more efficient hardware, 31 percent from improvements in cooling and power, and the single biggest chunk – 39 percent – comes from what Amazon calls "additional carbon-free energy procurement."

In fairness to Amazon, it is a huge investor in power purchase agreements (PPAs) for renewable energy and a huge investor in projects such as solar and wind farms. Indeed, it has invested in close to 500 such projects around the world according to Jenna Leiner, AWS's head of ESG and External Engagement. In Australia, that includes investments in Queensland, NSW and Victoria.

Leiner told Mi3 that Amazon is the world's largest procurer in this area and has been for the last four years.

These agreements effectively give renewables developers bankable contracts to secure finance to build out new clean generation, because the likes of Amazon are contractually committing to buy their power at a set rate over a number of years.

However, when these projects cannot fully meet energy demand, Amazon purchases renewable energy credits to offset any non-renewable energy consumption. These credits allow AWS to say that it matches 100 per cent of its electricity consumption with renewable power, even though the actual energy used may still come from a mix of sources on the grid.

It is easy to get lost in the nuance, says Lisa Zembrodt, principal and senior director, Schneider Electric Sustainability Business. "One of the issues is that these things can be a little bit complex and very difficult to explain.

"For every unit of renewable electricity that is generated and put into the grid, there is an electronic piece of paper. It's a certificate, and that certificate is what represents renewable electricity. So if a company has procured certificates equal to 100 per cent of their consumption then under the GHG Protocol, they have 100 eliminated their Scope 2 emissions over a year. Now, the finer details are that on a [given] day, did every five-minute interval of your electricity come from a renewable source? And the answer is, not yet. We're not yet there in our grid. It is an aspiration,"

Scrutiny increasing

The global hyperscalers are now running into problems as scrutiny increases on those claims.

The Financial Times in London, for instance, found that the bold comments by tech giants about their carbon emissions mask the real impact of their data centres on the environment. On Amazon, specifically, it referenced its claim to have met its goal of using 100 per cent renewable energy seven years ahead of schedule. Yet, in the United States, fossil fuels still contribute to about 60 per cent of electricity generation meaning that despite its green initiatives, Amazon remains a large emitter of greenhouse gases.

Likewise, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, claims to have achieved “net zero” emissions in its energy use. When the FT looked at its 2023 sustainability report it found its actual carbon emissions from power consumption last year were 3.9 million tonnes, significantly higher than the reported 273 tonnes.

A separate report in the Guardian found that "From 2020 to 2022 the real emissions from the “in-house” or company-owned data centres of Google, Microsoft, Meta, and Apple are probably about 662 per cent – or 7.62 times – higher than officially reported."

Google's own sustainability report reveals that its greenhouse gas emissions last year were 48 per cent higher than in 2019 which the company attributes to "increasing energy demands from the greater intensity of AI computing."

It says it currently sources about two-thirds of its energy from renewable sources. However, the US and Europe account for the lion's share of that, whereas APAC – including Australia – have a stronger reliance on carbon-intensive energy sources.

Microsoft acknowledges emissions are rising. In its 2024 sustainability report, Microsoft states: "Carbon reduction continues to be an area of focus, especially as we work to address Scope 3 emissions. In 2023, we saw our Scope 1 and 2 emissions decrease by 6.3 per cent from our 2020 baseline. This area remains on track to meet our goals. But our indirect emissions (Scope 3) increased by 30.9 per cent. In aggregate, across all Scopes 1–3, Microsoft’s emissions are up 29.1 per cent from the 2020 baseline."

According to the report, "The rise in our Scope 3 emissions primarily comes from the construction of more data centres and the associated embodied carbon in building materials, as well as hardware components such as semiconductors, servers, and racks. Our challenges are in part unique to our position as a leading cloud supplier that is expanding its data centres."

We blocked climate risk-related sites, resulting in a 25 per cent reduction in carbon emissions. Importantly, the campaign delivered a 27 per cent lower eCPM and a 70 per cent higher CTR. It turns out, reducing carbon emissions can also improve results for our clients.

Time-based advertising

Mandatory climate-related reporting will begin on 1 January 2025. The new legislation requires companies to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions and climate-related risks in line with international standards.

The timeline for compliance varies depending on company size:

- Large companies (with over 500 employees or significant assets and revenues) will be required to start reporting from January 2025.

- Medium-sized companies (with 250-plus employees or equivalent revenue) must begin reporting in July 2026.

- Smaller companies (100-plus employees or lower thresholds) will have until July 2027 to comply.

Additionally, companies have an extra year from their start date to fully report Scope 3 emissions, which cover indirect emissions from their supply chains and product lifecycles.

The Australian deadline for reporting is fast approaching but examples like NIB and University of Tasmania demonstrate how some brands are getting on the front foot.

Likewise, Opella Healthcare has won a clutch of awards for work it did with the Hearts & Science team to reduce the carbon impact of video advertising campaigns. Streaming ads globally emit 2.1x more carbon than display ads – however, in Australia, it’s up to 4x more than display, due to the fossil-dominated power grid. However that is now highly time-dependent, with high levels of solar at certain times combined with high levels of wind to effectively push coal and gas generation and therefore emissions – off the system.

At face value, Hearts & Science's Wong said there was "shock and horror" when the agency worked out "how much carbon, video advertising, was actually generating".

Hence there is a new interpretation for right ad, right place, right time.

"We saw the opportunity to go above and beyond measurement and built something that actively and real-time addressed how and when we ran ads – optimising our use of renewable energy and the carbon it emits."

That led the agency to build a Renewable Ad Engine, where the goal was to set up with a win, win, says Wong.

"We were thinking how about we find a way to deliver a campaign without affecting reach and frequency or the results of the campaign, but skewing towards periods of relatively higher renewables. We built the engine, we ran it, and we saw that we increased renewables usage versus a standard delivery of a campaign, a streaming video campaign, by 76 per cent.

"So that's a 76 per cent increase in renewables, and then I think carbon emissions off the back of that dropped by 33 per cent."

It's tricky, given the real-time nature of power generation and consumption, the vagaries of the weather and the differences at national and state levels. But "every little bit helps, and we thought, that's the first thing we're going to tackle because that's the biggest number that we can see in our plans due to the shift from linear TV into streaming," says Wong.

In another campaign, Wong says Hearts & Science blocked climate risk-related sites, resulting in a 25 per cent reduction in carbon emissions. Importantly, the campaign delivered a 27 per cent lower eCPM and a 70 per cent higher CTR. "It turns out reducing carbon emissions can also improve results for our clients," says Wong.

My own opinion is that we're not going to hit the climate goals anyway because we're not organised to do it... Yes, the needs in this area will be a problem. But I'd rather bet on AI solving the problem than constraining it and having the problem.

Lessons learned?

Discussing energy efficiency at a recent business forum, former Google CEO and Chairman Eric Schmidt made the point that there are basic architectural improvements that can be made to the grid, but that it likely doesn't matter in the age of AI.

"We've already discussed better materials for batteries, that takes a while, but that's important. You move to DC power lines for better transmission, loss control, and things like that. You build those things, [but] that takes a while. In terms of delivery of power, you work on power line losses. You put the data centers next to the big power lines.

"And architecturally, there are huge improvements to be made in essentially cost effectiveness, per transaction."

All of this comes with a huge qualification, according to Schmidt. "All of that will be swamped by the enormous needs of this new technology."

He told the attendees, "And because it's a universal technology, and because it's the arrival of an alien intelligence, something we don't understand, we may make mistakes with respect to how it's used, but I can assure you that we're not going to get there through conservation. That's the key point, and the economics will drive it anyway. No large company wants to have a huge power bill. Most of the people I've talked with say the power bill is becoming a very large component of their expenses."

Schmidt's solution - let the tech bros build as much AI as they want and burn as much energy as it takes.

Asked if we can meet AI's energy needs without totally blowing out climate goals, his answer was telling, but totally on brand for Silicon Valley, "The US uses less power now than we did and generates less CO2 of a bad kind over the last five or 10 years. So the industry and the regulatory structures are working to reduce on a percentage basis.

"My own opinion is that we're not going to hit the climate goals anyway because we're not organised to do it... Yes, the needs in this area will be a problem. But I'd rather bet on AI solving the problem than constraining it and having the problem."

Sure, but what if he's wrong?