Overcooked? MasterChef feels heat over renewable gas partnership; greenwash claims highlight ad industry's ethics gradient, critics point to 'soft' regulations and leadership void

MasterChef has debuted a ‘carbon neutral’ renewable gas kitchen this season, courtesy of a two-year partnership with Australian Gas Networks. But what might seem like a win for sustainability has been slapped with greenwashing claims from climate groups claiming Network Ten has sold out to a gas industry determined to delay the transition to an electrified economy. While that claim is on one hand justified, it overlooks the fact that the single largest component in Australia's power generation mix is coal, but it's just one case in what is an ongoing debate of where the line lies for the advertising industry when it comes to fossil fuels. Despite efforts by the AANA and ACCC to crack down on bad behaviour, critics say regulators are not equipped to deal with the nuances of some environmental claims. That leaves it down to the industry’s leadership to take a stance. Former OMD, Ikon and Mindshare boss turned net zero consultant James Greet says that’s just not happening in Australia, claiming some are "peddling the same pile of shit as the people that they’re working for". But the Albanese government is now backing hydrogen in a big way.

What you need to know:

- Network 10 and Australian Gas Networks (AGN) have come under fire from environmental groups for a new two-year partnership that has seen the MasterChef kitchen fitted out with renewable gas-powered cook tops – “embedding carbon neutral energy right into the heart of our production”, per Paramount sales chief Rod Prosser.

- The partnership, which has scored the wrong kind of attention in the mainstream media, is attracting greenwash claims over its promotion of poo-powered biomethane and 'carbon neutral' hydrogen as a "low carbon solution" to "support Australia's energy transition", per AGN customer and strategy lead, Cathryn McArthur. Critics suggest renewable gas can only play a bit part if net zero is to be achieved – they say it's a distraction from a more urgent transition to electrification of the economy. It's also not yet available to the retail market.

- Whether or not those claims are credible – bearing in mind Australia's power generation mix is dominated by more polluting coal, followed by gas, with only a third coming from renewable sources – it brings about an issue that Australia's advertising and media sectors continue to grapple with: whose job is it to keep greenwashing in check, and are there greater ethical questions to be asked about working with fossil fuels clients?

- ASIC has been taking action of late, hardening its stance against questionable environmental claims – to mixed feedback – while the ACCC two years ago put greenwash towards the top of its agenda.

- Belinda Noble, founder of pressure group Comms Declare, tells Mi3 that her organisation plans to put in a complaint to the regulators – though she's not sure which one. Noble and net zero consultant James Greet argue that the AANA and ACCC lack sufficiently explicit regulations to deal with nuanced cases.

- But AANA Director of Policy & Regulatory Affairs, Megan McEwin says the association's incoming Environmental Claims Code will close that gap.

- While AANA boss Josh Faulks has previously suggested advertisers are "terrified" of being probed over greenwash, McEwin said official advice to advertisers is to share positive changes without overcooking claims.

- None of the seven claims levelled at AGN's previous renewable gas campaigns since 2020 have been upheld by AANA's Ad Standards Panel. Likewise, the ACCC is yet to call out gas networks for making green claims.

- While the regulatory landscape plays catchup, Greet argues the buck stops with ad industry leadership – which he says has been lacking on the issue of climate change.

- He concedes current economic pressure makes it harder for agencies to turn down money, “But that’s leadership – [decide] whether you go for the easy buck or whether you apply ethics to what you do.”

- Meanwhile this week's budget suggests the Albanese government has significant faith in hydrogen to help hit net zero goals. Though whether anyone will be using it for cooking – outside of MasterChef – is highly debatable.

Hot water?

MasterChef this year debuted a ‘first of its kind’ renewable gas-powered kitchen fit-out for the program’s 16th season – complete with biomethane-fired stoves and hydrogen-fuelled barbecue tops courtesy of a new two-year partnership with Australian Gas Networks (AGN).

AGN, along with parent company Australian Gas Infrastructure Group and fellow gas supply companies Jemena, ATCO, Solstice, struck the partnership with Network 10 and MasterChef Australia production company, Endemol Shine, via a vehicle they’ve dubbed Renewable Gas.

In a media release announcing the partnership, Paramount Australia’s Chief Sales Officer, Rod Prosser, said it aligned with the media company’s “focus on sustainability” by “embedding carbon neutral energy right into the heart of our production”.

(Ten has arguably been the most committed to sustainability of all the major local broadcasters – which face a massive challenge to decarbonise given the huge carbon footprint of key components like production, and who until about 12 months ago faced constant pressure from media buying groups, notably GroupM, to decarbonise or lose ad dollars. But buyers have been less vocal of late.)

AGN’s executive general manager of customer and strategy, Cathryn McArthur, added that renewable gas allows Australians to “keep cooking the way we love with fewer emissions than natural gas” – “it’s a practical demonstration of a low carbon solution that can be delivered by existing gas networks to support Australia’s transition to net zero,” she said.

Gas networks and their investors (which tend to be pension funds and infrastructure groups) face an existential challenge from net zero – and around the world are trying to work out how to future-proof their business. But hydrogen has very different properties to methane and genuinely green hydrogen, produced via renewable/nuclear power via electrolysis, is costly and inefficient to produce, store and transport – and would likely require a major upgrade to both the gas grid and wholesale swap out of household boilers and appliances.

Nevertheless, gas companies are trying to make the case for hydrogen – and shows like MasterChef provide a vehicle. The problem is, the AGN-Paramount partnership has earned media coverage for all the wrong reasons, with critics suggesting the sponsorship overcooks the significance renewable gas can play in the energy transition.

Environment Victoria’s Climate Campaign Manager, Joy Toose, says the MasterChef integration “only helps to greenwash the gas industry and create a false impression that biomethane and hydrogen are good replacements for methane gas”. The group laments the missed opportunity to adopt electric induction stovetops, as has been done by MasterChef franchises in the UK, Italy, Singapore, Denmark, and Spain.

Network 10 and Endemol Shine wouldn’t be drawn on greenwashing claims, confirming only that, “The MasterChef Australia kitchen uses gas” and this season had “been able to use biomethane”. AGN did not respond to Mi3's requests for comment.

Money, power

The crux of the criticism comes down to renewable gas being seen as economically unviable for all but hard to decarbonise sectors such as manufacturing and heavy industry, given its scarcity and high costs and that MasterChef and AGN are promoting a product that household consumers don’t have access to, and probably never will. More broadly, critics argue that finding new avenues for gas acts as a blocker for a cleaner energy transition.

According to the FAQs section on the Renewable Gas website, “renewable gas is not yet available for direct purchase by consumers in the retail market”. On its website, AGN says it’s targeting 10 per cent renewable gas by volume by 2030, and 100 per cent by 2050.

Jamena, which supplies the biomethane used in the MasterChef kitchen, is behind the only demonstration project in Australia that’s currently injecting biomethane into the existing gas network, with the Malabar biomethane plant, which produces gas from sewage, capable of producing enough renewable gas to power 6,300 NSW homes, roughly 0.05 per cent of Australia's 10.9m dwellings, per ABS data. The firm is highlighting its contributions to the energy transition in a new campaign it commissioned from by IPG Mediabrand’s MBCS to run during MasterChef ad breaks.

While the Malabar plant is government certified as producing green power, the partnership has raised questions in some quarters around the advertising and media industry's dealings with the fossil fuel industry.

James Greet, a former agency boss with Mindshare, Ikon, OMD and senior exec at Cummins & Partners and Hero, now runs a specialist net zero advisory called The Payback Project.

He suggests agencies – and by implication media – should stop taking the money.

“The disappointing thing for our industry is that agencies are willing to play ball with and use the undoubted storytelling behavioural change capabilities that we possess, to continue to be a force for bad, when they could equally be pointed in the direction of better businesses and be used as a force for good,” said Greet.

Gas blast

Besides the fact that renewable gas isn’t yet available to consumers, the greenwashing claims thrown at Paramount and AGN echo findings that renewable gas is a distraction from the urgency of electrification, seen by many as the only genuinely viable clean option for decarbonising heat and transport (and cooking). But electrification via renewables and nuclear power will requires a total re-ordering of Australia's generation mix and massive scale up in generation. Renewable generation has quadruped over the last couple of decades but still represents only a third of the power going into the grid.

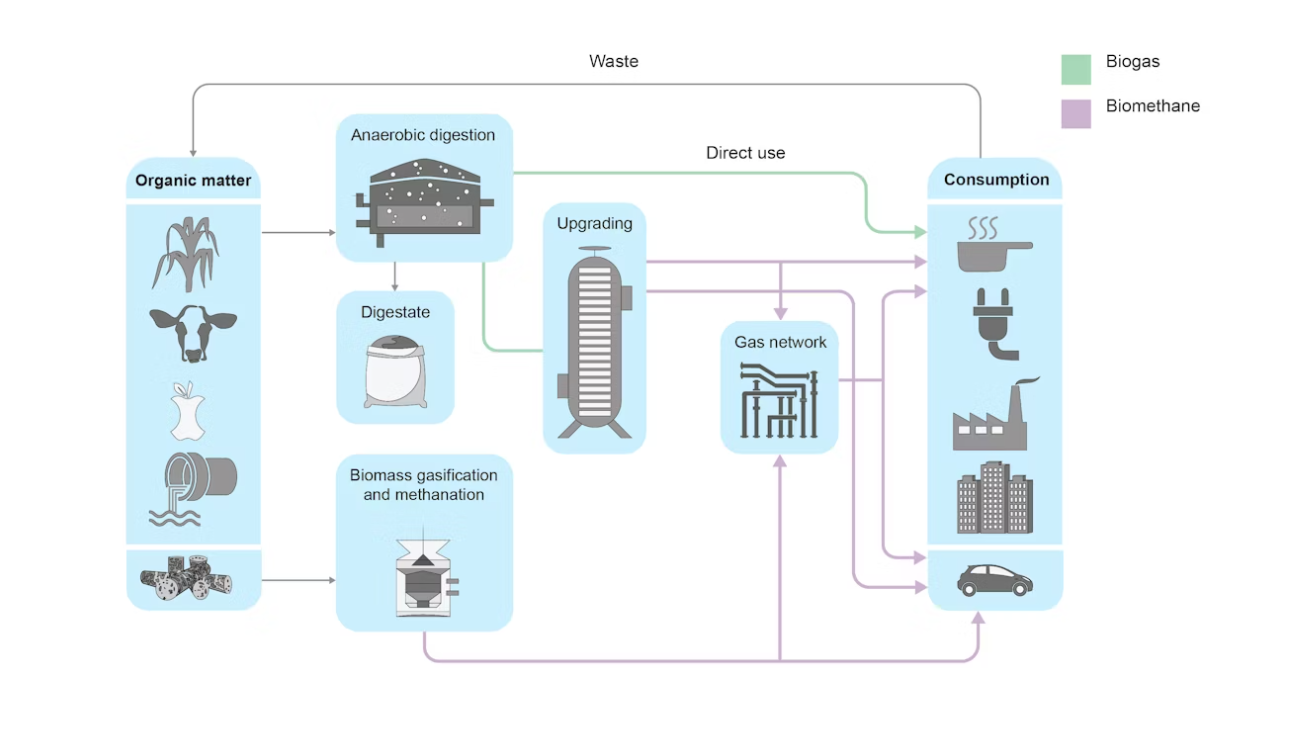

Renewable gas, according to Australian Gas Networks, is a term to describes gases – primarily biomethane and hydrogen – that “can be used as a clean energy source which does not produce any additional emissions when you burn them”.

Biomethane, or biogas, as it’s sometimes called, is captured from decomposing organic waste from landfill, agricultural, and wastewater treatment facilities. It can be blended with natural gas and distributed via existing gas network infrastructure.

The problem, per the Climate Council, is that “there is simply not enough biomass to generate the quantity of biogas required to replace our current usage of gas”. Thus, Australia’s Bioenergy Roadmap, published in 2021 by the Australian Renewable Energy Agency, puts biogas at 20 per cent of the total pipeline gas market at best by 2050.

Source: : International Energy Agency (2020)

Grey area

Hydrogen, on the other hand, is created by splitting water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. ‘Green hydrogen’, is created using renewable power via electrolysis – it’s the gold standard in terms of emissions, though expensive to produce, store and transport. Per the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC), most hydrogen is not emissions free, instead created via thermochemical reactions that use either coal (‘brown hydrogen’) or natural gas (‘grey hydrogen'). There's also 'blue hydrogen', which captures the emissions and buries them underground in a process called carbon capture and storage – but that has not yet been proven at scale anywhere in the world.

This week's Federal budget enveloped a multibillion dollar fund for green hydrogen, indicating the government views it as a viable option for economic decarbonisation. But around the world, the investments being made by energy companies into genuinely clean hydrogen are with major industrial companies – i.e. private pipelines direct to industrial sites to decarbonise heavy manufacturing like chemicals, steelmaking and manufacturing for highly energy intensive production processes.

Very few people think hydrogen will be used for cooking.

Nevertheless, it's grey hydrogen that’s being used in the current series of MasterChef, described on the Renewable Gas site as ‘carbon neutral’ hydrogen – presumably via carbon offsetting. Green hydrogen was made available on site after filming and is set to be used for the program’s 2025 season.

Much like biomethane, hydrogen gas, if it is used in the gas grid, would most likely be used as a blended product with natural gas – AGN is currently experimenting with levels of around 10 per cent. Current gas infrastructure can safely handle blends of up to 20 per cent hydrogen. Higher blends – or an entirely hydrogen-based system – would likely require a wholesale replacement of the gas grid.

Then there’s pricing. While both biomethane and hydrogen come in at a higher price point than natural gas, the latter is particularly eye-watering. According to the Australian Energy Regulator, wholesale natural gas prices sat at around $12 per gigajoule (GJ) in Q1 of 2024. Meanwhile, global averages put wholesale biomethane at around $17 per GJ, and hydrogen can sit anywhere from $83 to $125 per GJ in Australia (though it’s projected to be between $15 and $30 per GJ by 2030, but those assumptions make some heavy lifting in terms of scale-up).

So, what does this all mean in terms of a TV show facing a little heat, renewable or otherwise? Essentially, the greenwashing claims levelled at Paramount and AGN are less to with the use of renewable gas itself, but rather the fact that its rollout is directly tied to the continued use of natural gas, arguably running contrary to Australia's Federal and state-based net zero policy objectives.

Environmental groups are not the only ones who have taken issue with the gas industry’s preoccupation with renewable gas – a report published by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) in August warned the promotion of the natural gas alternative was against “the best interests of energy consumers”, aligning closer to their own "commercial interest in recovering their past investments, by continuing to supply some form of gas to their customers". (The IEEFA, while independent, does take funding from groups that favour electrification via renewables.)

According to the paper, electrification is widely accepted as the most cost-effective path forward for the “majority of homes to decarbonise their energy consumption”, with renewable gas “highly unlikely” to play a meaningful role is residential energy supply. Promotions that suggest otherwise risk blocking progress on the orderly transition to an electrified future", they said.

The IEEFA went on to warn that gas distribution networks were “exposing themselves to substantial risk” of investigation by the ACCC by pushing renewable gas campaigns that failed to acknowledge “the low likelihood of a significant role for ‘renewable gas’”, at least as far as household use is concerned. The Institute also points to the fact that the renewable gas narrative contradicts the dominant policy direction, which preferences electrification for homes – in Victoria (where MasterChef is filmed) the state government has banned gas connections for new homes from January this year.

Regulate this

The advertising industry has been under growing pressure to wash its hands of fossil fuels clients, but it’s complicated.

With greenwashing becoming more prevalent – as corporates look to enhance green credentials with consumers – industry and government regulators alike have been cracking down on bad behaviour.

On the self-regulatory side of the equation, as ever, is the Australian Association of National Advertisers (AANA). The AANA set about overhauling its Environmental Claims Code in late 2022, but critics have taken issue with “relatively soft” guidelines put forward in an Exposure Draft published in January. They say these aren’t equipped to deal with nuanced cases like the partnership between MasterChef and AGN.

“I think they're not fit for purpose at the moment,” suggests Greet. “If we're truly serious about change we need proper legislation and regulation and proper policing and management of it, like we've seen in the UK and in Europe – we're way behind, but we can catch up.”

Belinda Noble, founder of Comms Declare (the pressure group behind the Fossil Ad Ban), holds similar concerns. She says her organisation is currently preparing to submit a complaint to regulators, but she’s worried the current guidelines won't find technical fault with MasterChef and AGN. She's also not entirely clear which regulator to complain to. Regardless, she says it’s “disappointing” that agencies would foster what she and others perceive as a false narrative.

The AANA, on the other hand, assured Mi3 that the current code does cover future activities and requires substantiation of future claims – and the new code will deal with this more explicitly.

While reluctant to talk specifically about MasterChef, AANA Director of Policy & Regulatory Affairs, Megan McEwin, advised that “making a broad claim is dangerous if the claim only applies to one product or one part of a company”. Thus, the AANA’s advice to fossil fuel companies – and others – is to highlight the changes they are making without overstating their significance.

“It is important that consumers understand the carbon footprint and waste impact of the products they buy so they can make informed decisions and it is also important that companies see their competitors be rewarded or recognised for transitioning to a low-carbon and low-waste future, so they do the same,” says McEwin.

Nothing doing

As it stands, seven complaints levelled at AGN's renewable gas campaigns have been submitted to the AANA's Ad Standards Panel since 2020, and another against Jemena. None have been upheld.

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) sits on the other side of the regulatory equation. It told Mi3 that it doesn’t comment on “potential investigations or individual businesses”, and deferred to the environmental claims guidance it has published on the ACCC website.

Within that lengthy tome, there are a few points underlined by the watchdog that could be relevant in nuanced cases like this.

For instance, “don’t hide important information", and, "Consumers can’t make informed decisions if they’re not provided with relevant information that gives the full picture”.

There’s also a section about broad and unqualified claims that “can be interpreted widely and in different ways”. “Any limitations should be clearly and prominently disclosed and should not contradict the overarching claim."

But the precedent for cases like this is almost non-existent – Mi3 could not find any instances of the ACCC issuing infringement notices or fines to gas networks for environmental claims relating to renewable gas. Hence whether a complaint if made by Comms Declare to the ACCC would stand up is an unknown.

Complainants could maybe file with all regulators to be sure.

Where now?

While the regulatory environment as it relates to the climate continues to play catch up with community standards, Greet says the ad industry has in part been let down by a lack of leadership. Right now, “no one feels that they need to take responsibility because no one's going to put peer pressure on them”, he suggests.

“It comes down to whether or not leaders generally want to make a difference,” he says, pointing to the work done by the UK’s peak advertising body, the IPA – “the big client agency bodies came together and were very clear and unequivocal”.

“It's really hard for people to do that when they're running companies that are understaffed and money’s short, the market’s down and all that stuff,” he concedes. “But ... that’s leadership – whether you go for the easy buck or whether you apply ethics to what you do.”

That's perhaps easier to say when you are no longer running the local arm of a global holding company.

Omnicom-owned CHEP Network, the current media and creative agency of record for AGN, and IPG-owned MBCS, the creative studio behind Jemena’s renewable gas spot, both declined to provide a comment for this story. But it’s not uncommon for agencies to defend their work with fossil fuel clients under the premise of aiding their transition towards sustainability.

Greet suggests that these kinds of justifications are at their best “wonderfully naïve”, and at worst, “peddling the same pile of shit as the people that they’re working for”.

Not everyone takes the same hardline stance as Greet. Very few agencies have outwardly committed to avoiding fossil fuel-adjacent clients. As Greet points out, it's not the easiest time for agencies and media companies to be turning away big pay cheques. And as of this week, green hydrogen has another big cheque from taxpayers.

Whether anyone ever cooks with it remains to be seen.