Trust: you can’t fatten a pig on market day

When the corporate effluent hits the fan, should a company weather the storm or come out swinging? That depends, says Forethought Executive Chairman and Founder, Ken Roberts. There are different levels of organisational response ranging from a steady state to a passing concern, a troubling development, and a full-blown crisis. Either way, when an organisation’s risk committee talks about trust and reputational damage, they often have little idea about what attribute of trust is driving acquisition or retention and the extent that it matters. So now is the time to empirically prepare for that reputational crises – and how to do it, while you still have any trust to lean on.

On 25 October 2016, four riders on the Thunder River Rapids ride at the Dreamworld theme park in Queensland were killed when equipment failed and the raft they were travelling in collided with another raft.

The coroner found that management of Dreamworld was responsible for systematic safety failures. Dreamworld’s parent company, Ardent Leisure, was convicted and received a record fine. The park was closed for six weeks and the ride scrapped. The opportunity to build and maintain trust through appropriate safety practices for the one million guests a year had been foregone.

Compounding the tragedy, two days after the accident Ardent Leisure’s CEO told a media conference that the families had been contacted and support offered when, in fact, no contact had been made. The CEO then flipped and claimed that she had not contacted the families because she “did not have the family of the victims’ phone number”. Four months later, the mother of two of the victims revealed that while Ardent Leisure had said it was sorry for the circumstances she was in, it had not actually apologised. The absence of an appropriate apology had become a large part of the news story. This was no longer a matter of repairing the brand damage; it was now a question of ethics, morality and human decency.

The question here, however, is in terms of reputation and economic criteria, does an apology help to restore the brand or even just stem the damage? Based on purely those two criteria, no matter what some crisis communication and corporate affairs experts say, the CEO of a company that has breached the trust of the public should not apologise (unless there’s been an unlawful act). History and research show that when it comes to a public apology, the CEO is personally worse off and facing permanent reputational damage, while the organisation fares no better than had no apology been made.

When a crisis hits, should a company weather the storm or come out swinging? The more assertive approach should be considered only if you think the mob can be swayed. Most organisations wait for the mob to lose steam and then start the brand rebuilding work. In most cases, the restoration of trust through forgiveness and forgetfulness can take up to 18 months.

Trust is related to all forms of organisational citizenship such as altruism, civic virtue, inclusiveness, conscientiousness, environmental, social, and governance matters and courtesy. But are these the elements that drive purchase behaviour? Commentators often claim that poor corporate behaviour undermines people’s trust. That might be so, however, any consequences to business outcomes depends on whether the poor behaviour impacts on a driver of consumer trust and, if that driver is related to purchase behaviour.

When the law firm Maurice Blackburn attracted sustained media attention for paying its partners ahead of the plaintiffs in one of its class actions, research found that did not undermine the firm’s trust scores. Prompt settlement of damages was not a driver of trust; successful litigation was a driver of trust. The advice Maurice Blackburn followed was to weather the negative attention.

When an organisation’s risk committee talks about trust and reputational damage, you can be reasonably certain that they do not have before them an empirical model of trust drivers. Intuitively, they might feel that trust matters but they often have little idea about what attribute of trust is driving acquisition or retention and the extent that it matters.

Trust is an abstract noun but, moreover, it is an abstract concept. Brands frequently make trust an organisational goal, however, they have little or no empirical evidence of how to build trust. The drivers of trust are entirely dependent on who is defining it and the circumstances at the time. Trade unions, regulators, law makers, colleagues, prospective colleagues, customers, or prospective customers may all have different definitions and expectations.

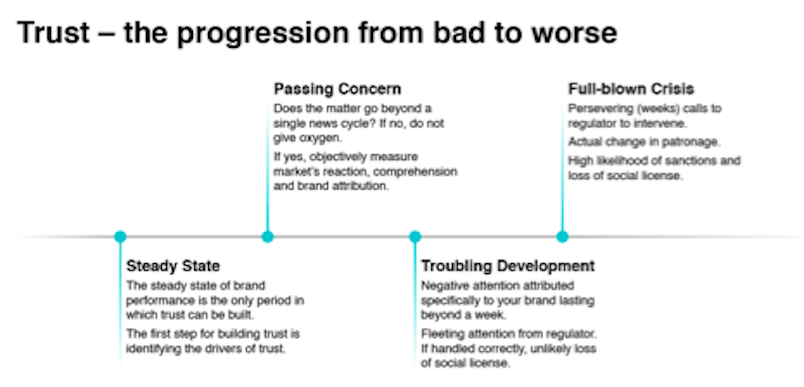

The circumstances for trust vary from the steady state to a full-blown crisis. There are different levels of organisational response ranging from a steady state to a passing concern, a troubling development, and a full-blown crisis.

Different situations require different responses:

During times of crisis, as the organisation’s trust performance falls, we have frequently witnessed the relative importance of trust as a component of brand in the form of future purchase behaviour markedly rise.

Factors that drive trust during the steady state are not necessarily what drives a rebound in trust in the middle or the aftermath of a crisis. In the case of one client suffering a significant data breach, five new significant category drivers entered the predictive purchase model.

These new drivers are not drivers of trust. They are recovery drivers. For example, “protects customers’ data” is not a reputation driver but rather a performance driver. For the organisation to reenter the consideration set it must address these new drivers.

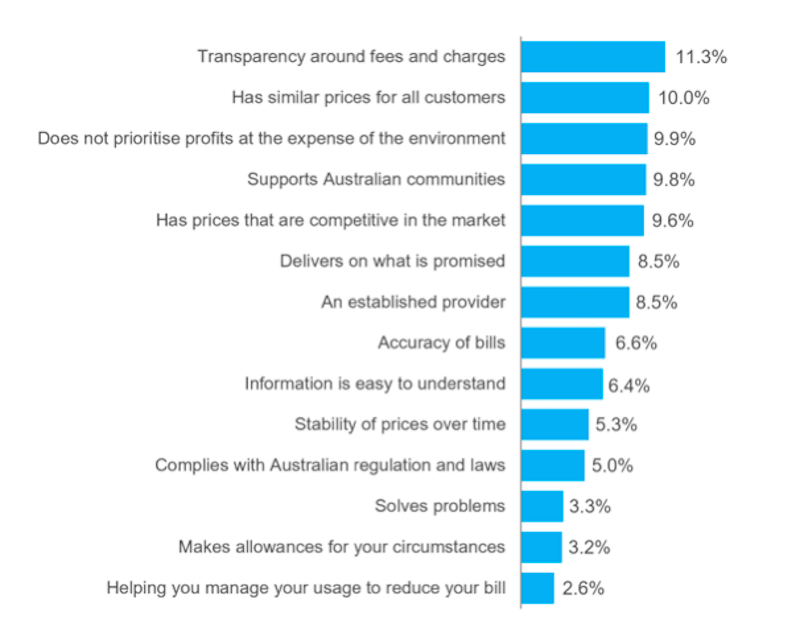

The only time to build trust is during the steady state, so identifying the drivers of trust during this period should be mandatory for brand management. The following chart illustrates what lies beneath the abstract concept of trust for an energy retailer during a steady state. Having deconstructed trust, the organisation is now ready to set about to build a store of trust. To repeat, trust can only be built during a steady state.

Relative importance of drivers of trust

If you currently do not have a trust issue, then prepare now for having one by quantifying the drivers of trust and incorporate them into organisational behaviour and marketing communications. Organisational trustworthiness equals stored value in the form of forgiveness. Forgiveness is the market’s preparedness to regard wayward behaviour as an aberration. For those categories where trust is important to consumer choice, remember that you cannot fatten a pig on market day.

Trust is part of brand and, like goodwill, it must be stored.

To build trust, organisations must first quantitatively deconstruct trust into its constituent pillars and explanatory variables, model the importance of the hypothesised variables, select trust drivers and then set about to build trust. This requires establishing the drivers that relate specifically to who they want to trust them and for what purpose.

Lastly, communications need to be tested for plausibility and coherence. Organisations are often alarmed to discover that due to a loss of trust, cynicism towards all communications is so high that communication may be an utter waste of time – including apologies.