‘Really mediocre outcomes’: Oxford Uni professor says Byron Sharp and Ehrenberg-Bass’ marketing science rules no longer hold – 1,000 campaigns, 1 million customer journeys as evidence

Academic resistance: Oxford University v Ehrenberg Bass on moving marketing science.

Associate Professor Felipe Thomaz, of University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, suggests Professor Byron Sharp’s best known book, How Brands Grow, is a misnomer – it’s actually about how big brands keep big marketshare, not how they got there. He also says it’s based on flaws within Andrew Ehrenberg’s earlier work, primarily static markets and a requirement not to differentiate. Thomaz suggests that’s why FMCG firms adhering to those rules were caught napping by more nimble differentiated start-ups. Optimising media for reach alone no longer works, he suggests, because all reach is not equal – and used bluntly won't deliver business outcomes. “There is a missing dimension,” per Thomaz. He’s out to prove it with a peer-reviewed paper that analyses 1,000 campaigns and a million customer journeys via Kantar and Wavemaker. The upshot? “None of it holds … I'm seeing that 1 per cent of campaigns are actually getting exceptional money, while the vast majority are choosing to get some really mediocre outcomes.” But there's potential upside for marketers, media agencies – and media owners – that grasp the category-specific implications.

What you need to know:

- Associate Professor Felipe Thomaz is in Sydney this week for South by Southwest.

- His session yesterday was about challenging marketers, agencies and media companies on their unwavering adherence to audience and customer reach as a baseline strategy for advertising comms and broader marketing activities.

- Thomaz says reach has maxed out and close to optimal industry wide – and his analyses of 1,000-plus campaigns and a million customer journeys via Kantar and Wavemaker data shows optimising for reach rarely tallies with business outcomes.

- In fact, only one per cent of campaigns delivered meaningful double-digit business lifts. The average was sub two per cent.

- That’s because there are distinct category nuances that apply to each channel, and that all reach is not equal.

- For instance, and specifically for lower funnel performance, he says TV only has a two per cent chance of influencing an auto customer. But it has a 50 per cent chance in personal care. And there are some interesting non-category specific findings for channels like influencers, which in lower funnel terms, is trumped by print ads.

- Thomaz is directly challenging the core work of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute and Professor Byron Sharp’s most famous book, How Brands Grow. Thomaz suggests it’s a misnomer, that Andrew Ehrenberg’s work is flawed when used as a marketing strategy, and claims few in academic circles take concepts like mental availability seriously.

- Thomaz hopes his paper, undergoing peer review for the last two years, will be published in the Journal of Marketing early next year. He also hopes it will change how marketers make media investment decisions – and help publishers realise that their specific category nuances can be sold at a premium.

- But how to get hold of the required data to make that shift – and how to effectively action it – is not entirely clear cut and no mean feat in an industry still grappling with cross-channel measurement and incremental reach.

- There’s more nuance and detail in the podcast. Get the full download here.

Concepts … like ‘mental availability’ don't feature in academic theory, at least at the highest levels [within] journals that have the strictest peer review requirements.

Over reach?

“You come at the King, you best not miss”, was Mark Ritson’s advice to Felipe Thomaz. But the Oxford University associate professor is undeterred – and he’s coming at professor Byron Sharp and Ehrenberg-Bass again, this time at SXSW in Sydney ahead of a peer-reviewed paper next year which he hopes will prove “reach sufficiency”, or optimising media for reach alone, no longer works. He says “it’s dangerous” – and more broadly that eschewing brand differentiation is well, plain wrong.

Thomaz’s latest work, based on analyses of 1,000-plus campaigns and a million customer journeys via Wavemaker and Kantar data, also throws up some interesting category buyer differences that should have media owner commercial chiefs rubbing their hands and working out how to sell at a premium within some categories versus blanket reach-based plays.

While Thomaz doesn’t talk specifically about attention, there appears to be directional parallels with professor Karen Nelson-Field’s work. As Nelson-Field states: “Impression relativity and measurement clarity is a thing of the past … While I agree reach is valuable to brand growth, error significantly reduces the ability for reach-based planning to even work”.

In other words, there is layer upon layer of nuance to consider across channel and category beyond reach and possibly frequency too. Thomaz has apparently found a kink in the long-held wisdom, seemingly backed by plenty of evidence. But the question remains: how do marketers act on it and extract 'influence-ability' effects, or propensity and influence scores, from the data they have on hand? The industry is struggling with basic cross-media measurement for incremental reach, let alone incremental influence. How Brands Actually Grow might be a useful next marketing science tome.

The original [Ehrenberg] model requires stationary markets … It requires that your market share is not changing, and it requires that the products are undifferentiated.

You're making suggestions of how to change market share on the basis of a model that cannot handle change, or whose main assumption is that the market share won't change. So that’s a problem.

Outgrown assumptions?

Felipe Thomaz has a problem with How Brands Grow, Byron Sharp’s most famous work.

“The underlying work is very solid, but of limited use, and the interpretations that come from that work have outlived its usefulness,” he ventures. “From time to time, if not almost always, they break fundamental assumptions of the original [Andrew Ehrenberg] research. So you can't use those results in the application.”

Thomaz says Ehrenberg put “warning labels” on his original research, effectively stating that it was not about how marketers “do” marketing, but how marketshare works in the marketplace.

Ehrenberg’s work and models on repeat buying patterns “is remarkably robust”, says Thomaz. “It shows results with remarkable reliability, it worked really well and academia took that to heart.”

The problem, he suggests, is Ehrenberg's model is “of limited use, because it tells us nothing about how to achieve market share, or change market share. It literally just says, ‘The bigger you are, the better off you are’ … And if you've convinced yourself that you want to be bigger, and you've convinced yourself that distribution is important in that process, I think you can then move on from that theory.”

Hence he says How Brands Grow is a misnomer. “How you stay big” would be more accurate.

“In a sense, it’s really attractive as an idea for the marketplace, because you can say, ‘if you follow this one simple rule, or a few simple rules – if this, then that – then your marketing is sorted’.”

Per Thomaz, “simplifying complex social systems to something that reductive is attractive, because you don't have to think really hard. But ultimately it carries a high degree of risk and error.” He says “for the vast majority of academics, the fact that this is the core idea would be a sheer surprise” but that due to a lack of peer review, “academia hasn't paid attention to it in the least”, he claims.

“Just to make it very explicit, the original [Ehrenberg] model requires stationary markets … It requires that your market share is not changing, and it requires that the products are undifferentiated,” he says.

“You're making suggestions of how to change market share on the basis of a model that cannot handle change, or whose main assumption is that the market share won't change. So that’s a problem in application.”

Thomaz suggests that’s why large CPG firms and the multinational brewers that followed the Sharp/Ehrenberg-Bass playbook, because it tallied with their short-term sales data, were ambushed by nimble differentiated start-ups, direct-to-consumer players and microbreweries.

“That death by a thousand cuts, by a thousand differentiated small brands, seems to be a direct indication that these things don't work,” he says. “My research has shown it time and time again that this is a folly.”

I'm seeing that 1 per cent of campaigns are actually getting exceptional money, while the vast majority are choosing to get some really mediocre outcomes,

Mental deficiency?

Ehrenberg-Bass and Byron Sharp have long banged the drum for marketing to be considered a science. Thomaz agrees it is a social science, but as social systems evolve, the science must evolve with them. Meanwhile, he says academic peer review at the highest level, rather than seeking validation in mid or lower ranking journals, is paramount for scientific credibility.

Thomaz suggests “concepts … like ‘mental availability’ don't feature in academic theory, at least at the highest levels [within] journals that have the strictest peer review requirements”.

Thomaz says he’s not sure why some marketing scientists might avoid top-level academic scrutiny, but his forthcoming paper has been under peer review for the last two years, with a team of professors “desperately trying to prove us wrong”. Good, he says, because that’s how science works, “and in every round we prove our results hold”. He’s hopeful it will be published early next year in the Journal of Marketing – and help put to bed the argument that “all you have to do is reach everybody” and be always-on.

“A lot of really problematic media planning strategies come from that,” he says. “There's not a single solution to this problem … You actually have to be a bit more intelligent about optimisation and planning.”

Reach vs. outcomes

Thomaz’s research looks at reach impacts and “cross-media complementarity” – i.e. how multiple media channels in combination deliver more powerful effects, an idea Sharp has previously suggested is “a bit of a myth” and “not evidenced-based at the moment”. It spans over a thousand campaigns with an average media spend of USD$12m that ran for circa five years. It doesn’t have sales data, but uses purchase intent as a proxy for sales and thereby enabling a read on lower funnel actions.

The research basically deploys a form of econometric modelling called stochastic frontier analysis. Thomaz explains it in investment terms:

“You create a portfolio of assets that will give you the most possible return. Your portfolio is efficient if it's giving you the most return with the lowest volatility or risk associated with it. Then you can trade off on that [i.e.] you can accept more risk for higher pay off – and that's the frontier curve. You're just trading on risk preference, but you're doing the best that you can possibly do. I just equated that to media allocation,” he says.

“I have in that paper, 11 different media channels that I can choose to buy, and I want to get the most lift out of that combination with the lowest risk … But I also had the reach associated with those campaigns and the combination of channels that would give me the most reach.”

Then he compared the two curves – reach versus business outcomes.

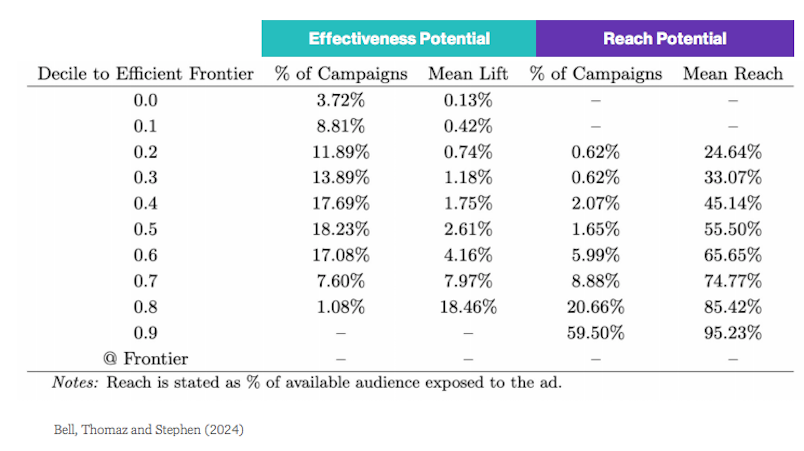

For the former, “over 80 per cent get to about as good as they can get on reach – 95-96 per cent reach of whatever they specified as their customer target base. So to me, that says managers are actually buying on this. They're working on reach, and they're optimising on reach, otherwise you would not have that obvious clustering.”

Bell, Thomaz and Stephen (2024) via Wavemaker data, 1,000-plus campaigns.

But across that dataset, ‘good as you can get’ reach does not equate to ‘good as you can get business’ outcomes. In fact, nowhere near. “That was the upsetting one,” says Thomaz. On average, all of the reach was leading to a sub-2 per cent business lift, whereas an optimised portfolio was getting “between 15-18 per cent lift”. But these were basically the one per cent club, says Thomaz.

“I'm seeing that 1 per cent of campaigns are actually getting exceptional money, while the vast majority are choosing to get some really mediocre outcomes,” he says.

“That to me was the biggest punch in the face on this idea of what I'll just term as ‘reach sufficiency’, which is this idea that if I do this, everything else will follow,” he says. The disconnect means “there is a missing dimension”, i.e. that not all channels are equal in their impacts.

We have a huge amount of heterogeneity across consumers, meaning that people are very different on how easily they are to be shifted from their preferences, and also that every channel has a different distribution or different characteristic on how powerful it is to influence people ... [meaning that] for some categories, there might be a premium [media owners] can charge.

Journey mapping

To try and prove that theory, Thomaz then analysed a million customer journeys, mapping 72 touchpoints “that influenced or had a role to play into that decision-making.”

In essence, Thomaz suggests it disproves the notion that reach is all that matters – because it shows all reach is not equal. “None of it holds,” he says.

“We have a huge amount of heterogeneity across consumers, meaning that people are very different on how easily they are to be shifted from their preferences, and also that every channel has a different distribution or different characteristic on how powerful it is to influence people,” he says.

Plus, there are variances by category in how hard or easy people are to “manipulate”. Which therefore has impacts on channel effectiveness and weighting.

Thomaz says that is good news for media owners – if they can stop selling on impressions and start selling on functionality. “For some categories, there might be a premium they can charge.”

If you want to be simple, enjoy your 2 per cent ROI. If you want to think about things with more concrete detail and that are more specific, and you want to exploit arbitrage opportunities in media, enjoy your 15 to 18 per cent.

ROI choices

Thomaz says reach is still important. “You still need to find your audience and you still need that scale. However, you also need your functional [goal]: What are you trying to drive with the brand? What is the business outcome? So it's this dual optimisation, it's not one or the other,” he says.

“Once you identify your objective, there's going to be an optimal combination of channels that will give you that objective with the highest efficiency. It's going to be the cheapest with the highest lift and the lowest risk. From that you can actually then deviate from the best in order to optimise your reach – so then you can scale that optimisation to the largest number of people,” adds Thomaz.

“There's a lot more available nuance, and there's a lot more money on the table if you choose to use that nuance. So if you want to be simple, enjoy your 2 per cent ROI. If you want to think about things with more concrete detail and that are more specific, and you want to exploit arbitrage opportunities in media, enjoy your 15 to 18 per cent.”

In every mix, there was only one channel that delivered across all goals, and that was television … it's consistently the best performer … it's a good fundamental base for everything that you're going to do.

Channel vs. category

When it comes to lower funnel performance, Thomaz says the data sets used within his paper throw up some interesting channel variances.

“In auto, for example, TV has about a 2 per cent chance of influencing the average person. But in personal care, it will have about a 50 per cent chance,” he says.

“If you're then using it for brand building, that would be a different percentage. And if you don't have goal-specific campaigns, then that's another problem that you have, because then you're further averaging things out.”

On a non-category specific average, he says influencer channels have circa 9 per cent chance of activating consumers to an immediate conversion. So if not lower funnel performance, what is influencer good for?

“I think they would be doing most of their work and lift on creating associations and making brands relevant for their audiences, which would be more upper funnel,” he says.

Some of the big CPGs like P&G have increased investment in influencer channels, particularly for their smaller brands, and Thomaz says that’s a good thing if they are trying to “increase the probability of the brand being included in the consideration set” or remaining in that set.

“But if the CFO comes in and says ‘I need x more million dollars this quarter from this brand, that's not the channel that you would turn on. Actually, print ads have 13 per cent [chance of influencing the average person].”

The key point is that the research underlines that each channel is “valuable and important in their domain,” says Thomaz.

While TV may compare poorly on immediate lower funnel conversion for auto brands, his paper, when released next year, will likely have TV networks and their respective industry bodies citing it at every available opportunity.

“In every mix, there was only one channel that delivered across all goals, and that was television … it's consistently the best performer … it's a good fundamental base for everything that you're going to do.”If you're managing your company's marketing on simplistic and reductive laws, you might want to revisit those, because you're leaving money on the table or leaving yourself open to very simple counter plays. It's dangerous.

Anyone care?

The question now is whether the research scales and whether marketers decide to take it forward – and crucially, how they do that.

“It’s for marketers to decide whether they want to use it or not,” says Thomaz. “There’s a potential for a domino effect – and the data [the research is based upon] exists in the marketplace.

“If you look channels as a bundle of both who's in it and what it does, then you can start buying it more intelligently. Similarly for media planners, [it’s about] pushing back against those generic plans that will drive every single KPI,” he says. Or at least recognising that crowbarring too many outcomes into the plan will end-up watering everything down – and that it might be better to focus firepower on one KPI and smash it.

His key take-outs for marketers?

“If you're managing your company's marketing on simplistic and reductive laws, you might want to revisit those, because you're leaving money on the table or leaving yourself open to very simple counter plays. It's dangerous,” per Thomaz.

“Within media channels, simplicity is hurting us. If it was true that reach sufficiency held, then we would all be replaced by algorithms overnight, because they can buy more reach instantly, and they don't need marketers to think or organise through the data and the complexity or context,” he says.

“Thankfully, none of that is real. It is part of the job, so we’ve been doing half of what we could do, but there's at least one other dimension that we can exploit. That is, depending on your goal, depending on your context – largely category context – then you can find way more money out of the market than you would have thought possible.”

I see a huge incentive for media owners. If you're Meta, you can now say, ‘not only do I have this audience, but my channel does this really well in your category, and no other channel provides that benefit’. So they have a much better justification for budget that they're trying to steal from the likes of Google or Amazon, retail media, wherever...

Publisher incentives

Thomaz is hopeful that some early adopters will create a trickle-down effect.

“Those companies will start seeing better ROI across all of their media spend, at which point they can maintain level with lower budget requirements, or they can just get better market performance with the same underlying budget,” he says.

“If that becomes a norm, then media providers will be selling on that basis as well – and I see a huge incentive for media owners. If you're Meta, you can now say, ‘not only do I have this audience, but my channel does this really well in your category, and no other channel provides that benefit’. So they have a much better justification for budget that they're trying to steal from the likes of Google or Amazon, retail media, wherever it might be,” suggests Thomaz. “So that information will spill out … and as that happens, I expect more and more people will use it and that just becomes our norm.”

Missing pieces

All well and good, but where do marketers start? Where and what are the data sets they will need?

Thomaz admits that’s not easy – and some would argue his answer is not entirely fuzz-free.

“[Marketers are] going to have a really hard time seeing the generalisable effect from your narrow data, because you're only going to know your own history – so you won't know things that you haven't explored,” he says.

“But that’s the sort of data that you should be looking at – media effectiveness and planning, any lift studies that you have done, stuff around MMMs [marketing mix models],” he adds, though noting MMMs are fraught with configuration issues. “But it's those media planning and cross-media effects, if any kind of data to validate your choices exists, that's the first protocol.”

Thomaz’s research also heightens the incentive for businesses to share long-term sales data and map it precisely to media agency channel planning and investment – often a challenge with MMM implementation. The downside is it may expose some inherent conflicts within those choices, especially where brands have signed-up to non-disclosed models.

But that’s a whole other story.