$700bn delusion: Does using data to target specific audiences make advertising more effective? Latest studies suggest not

Ever wondered how come martech is a US$700bn industry, but the ads you see are still crap? Clue – it's because the data foundations are crap, says Brand Traction's Jon Bradshaw. Following former UM privacy chief Arielle Garcia's takedown of the "garbage" data broking sector, Bradshaw challenges industry to provide proof that data-driven targeting actually makes advertising more effective – or in fact makes it worse. He's spoiling for a debate – and has three deep, recent studies that show: broad reach beats targeting for incremental growth; that the cost of targeting outweighs the return; and that second and third party data does not outperform a random sample. First party data does beat the random sample – but contextual ads massively outperform even first party data. And they are much, much cheaper. Now, says Bradshaw, let's see some counter-evidence from those making a killing.

Show me the data

Targeting our advertising messages to the right people, in order to make the message more relevant, and therefore more impactful, and therefore sell more stuff, is an advertising idea as old as time.

Right person, right message, right time.

Right?

Or is it?

Even if you have some questions about that as a broad generalisation, surely it's especially right for online and other “performance” ads where we are hoping to get an action, like a click, as a precursor to some form of “buy” action.

Surely, we can agree (or at least park the idea) that Byron Sharp’s sophisticated mass marketing, for long-term brand advertising might be right answer, but we segment and target for sales activation and immediate results. A little bothism, to quote another argumentative professor. And that to do that we need some data-driven clever approaches.

Surely, that’s right?

Surely?

Isn’t refined data-driven targeting the very point of digital? And CRM? And martech? And big data. And programmatic?

All the hoo-ha about privacy must be worth it because we get to do, right person, right message, right time – and that makes things more effective, right?

Right?

Surely, we are doing all those difficult, and contentious, and expensive things for good reasons?

Surely?

You’d be stupid to think otherwise.

Surely.

Mi3 two weeks ago unpacked what perhaps should be felt as jaw-dropping insights from Arielle Garcia. This poacher turned gamekeeper has a clear view on whether programmatic is a good thing (clue, reader, it isn’t) and why agencies and publishers and tech companies have been supporting it (clue, reader, follow the money).

Arielle, a former chief privacy officer at UM in the US, got her own data from a broker and found that she was in 500 different audience segments, both a man and a woman, worked in food service, agriculture, but was also a defence contractor, an engineer and was simultaneously below the poverty threshold and classified as high income.

Ever wondered how come martech is a US$700bn industry, but the ads you see are still crap? (Clue, reader, it's because the data foundations are crap.)

Maybe jaws shouldn’t be dropping. Maybe we should be nodding sagely along, going, “well, yes, we know this”. These “revelations” last week, are part of a highly congruent series of findings and evidence about whether the data and tech dream for advertisers is realisable, sensible and profitable or not (clue reader, it isn’t).

Here are three such congruent studies that suggest we should perhaps not be surprised that the programmatic dream might actually be a nightmare.

Firstly, in “Overwhelming targeting options”, 2023, Ahmadi, Nabout, Skiera, Maleki and Fladenhofer, look at the increased impact targeted advertising needs to make if it is to offset the costs of targeting. Clue reader, it might be actually be more profitable not to target.

Secondly, “Is it wise to prioritise #Reach over #Conversions?” from Rikard Wiberg at PACE in Stockholm, looks at whether using data to actively targeting a Meta buy against people more likely to convert performs better than simple broad reach in Meta platforms. Clue, dear reader, broad reach works best.

Thirdly in, “Is first- or third-party audience data more effective for reaching the ‘right’ customers?”, Nico Neumann, Catherine E. Tucker, Kumar Subramanyam, and John Marshall, look at how accurate first-party, second-party, and third-party data actually is at targeting a specific audience segment, and compare that with other less data-led ways of targeting. Clue, dear reader, that data is truly, really, just fucking awful.

These are early forays into these areas as far as I can see. So, we can critique the fact that they are experimental results, that need replication and extension, to see if we can form more broadly applicable principles, rules or laws.

We would be foolish to say these things prove truths.

But they are still evidence that points us in a direction.

A direction somewhat counter to the prevailing way the industry is heading. Or has been heading anyway. It is, however, a congruent direction, with some of the more established and more broadly applicable findings we have from the wider body of marketing science.

- If we accept that buyers are cognitive misers who expend the least mental and physical effort they can, to get their goals adequately met.

- If we can agree that advertising is weak force, that works best when it just makes buyers' lives mentally and practically easier.

- If we can agree that advertising works much less well, when it tries to be a powerful and persuasive force.

- If we can agree that those ideas are broadly evidenced and are likely to be “true”. Whatever true, means.

Then these findings stack up nicely with that world view.

So, debate the rights and wrongs of these conclusions as you will. There is debate to be had. Please provide counter evidence that refutes these findings – that would be fun.

But note the word evidence, not opinion.

Data. Peer review. Proper experiments. Replication. Econometrics not last click attribution. You know, something approaching decent professional standards. If you can do that, have at it.

Not versions of, “…but this one time, at band camp…”.

There is a heap of nuance and context that definitely needs adding to any points that can be made from these findings. So, let’s just accept that there is some grey here.

My approach, however is always, is to look at new evidence, check if it fits with the other things we know, and if it does, start to work out how to apply it, albeit maybe cautiously and experimentally.

The opposite view seems to be an even stupider way to operate:

- See new evidence.

- Go, “I don’t like that, because it’s not what I am currently doing or believe”.

- Keep on keeping on, with no actual basis for your current tactics, other than, “If I was wrong about this, I’m gonna look pretty stupid”.

Personally, I have accepted that looking stupid is just a big part of my life that I need to learn to love. I call it learning, because it makes me feel better about myself. Stupid I know.

So, let’s look at the studies in a little more detail.

1. Overwhelming targeting options

Ahmadi, Nabout, Skiera, Maleki and Fladenhofer’s work is one of the few I have found that looks at the costs of targeting, as well as the impact.

It harks back to my favourite quote from Erwin Ephron,

“But here we address the larger question: what is the best way for a brand to spend the money?”

Aye, there’s the rub, indeed. Does data-driven targeting represent a better way to spend the brand’s money?

If we assume targeting is more efficient, we still need to know if it is more effective.

The study shows that good targeting can lead to an increase in click-through rates. Excellent. Thank fuck for that.

Do you sense a but, dear reader? You should. And it’s a big one. When you add in the costs of targeting things look a little different.

Approximately half of those audience segments require the click-through rate to double compared to an untargeted campaign, which is unrealistically high for most ad campaigns. Our model also shows that narrow segments require a lift that is likely not attainable, specifically when the data quality of these segments is poor.

Targeting can boost click-through rates, if that's what we want. (Clue, dear reader, the answer is not always yes.) The increased creative and media costs of targeting, coupled with the reduction in reach, however, makes payback look much less likely. A cheaper, simpler, more mass-targeted campaign, is actually more likely to deliver a better return.

Being broadly effective, but somewhat inefficient, is better than being narrowly efficient, but less effective.

Targeting can increase the scale of effects, but this study suggests that the cheaper approach of not targeting so specifically, might actually deliver a greater financial outcome.

Which is, you know, kind of the point of advertising. To make people more money. I know we don’t often like to admit that as a profession, but we really do need to get more comfortable with the idea that advertising needs to make a profit.

Obviously, we need a lot more replication, but the findings don’t seem counterintuitive or counter to the other things we know.

2. Is targeting people who are likely to convert more effective than broad reach campaigns?

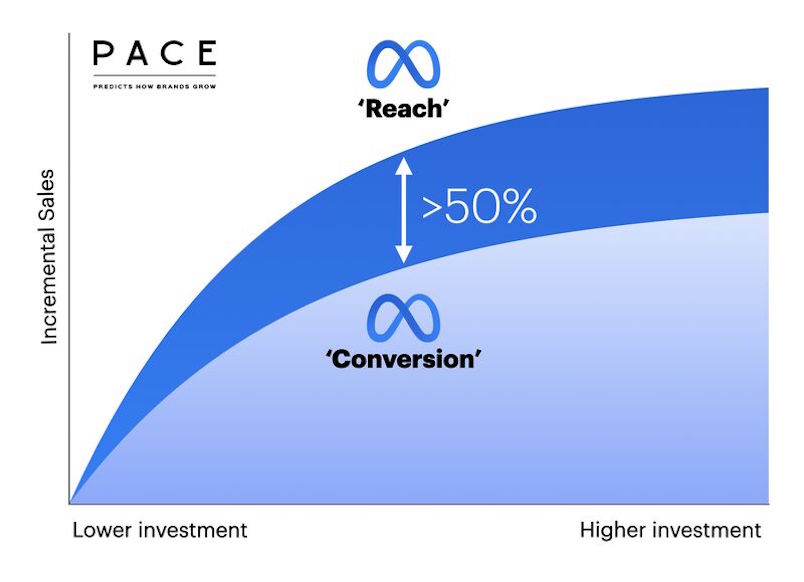

Rikard Wiberg a partner at Pace, a marketing science analytics and strategy firm in Stockholm, recently published the results of an experiment they undertook on campaigns that operated on Meta’s platforms.

In the study, they reallocated major investment from optimising conversions to just optimising reach, inside the Meta network, across three different markets. They then undertook market mix modelling (MMM) analysis to see which delivered the most incremental sales.

If you’re playing along, by now you can probably see where this is going.

Wiberg’s experiment showed that broad reach was at least 50 per cent more effective in driving incremental sales, almost regardless of investment scale.

The key word here is incremental. As Wiberg’s findings point out, the problem with targeting towards conversion optimisation is you are effectively advertising to many people who were already going to buy you.

Targeting against conversion-optimised audiences is the digital equivalent of handing out 50 per cent off discount vouchers to people just as they enter your shop.

Rather than reducing wastage, targeting is actually increasing the percentage of wasted impressions in the buy – if we look through the lens of incrementality.

Which, you know, we should. If we are about making more profit.

Counterintuitively perhaps, reaching more people, by targeting less, increases effectiveness. It does not reduce it.

3. Is first- or third-party audience data more effective for reaching the ‘right’ customers?”

But what about genuinely niche audiences?

If my audience is quite specialised, I really do not want the wastage that can come with “mass” media. There are hundreds of cases where you can rightly say:

“The notion that I should not target my advertising bears no connection to the reality of my business and the narrow segment of people I actually need to talk to.”

There’s some of that nuance we were discussing earlier. Sometimes you need to target your media buy.

If I only sell to IT decision-makers, for example, I need some targeting, as I just can’t afford to talk to random consumers. I must pay for some targeting in my media buy, in order to reach a relatively niche audience.

Targeting is no longer a nice to do, but a must have.

The interesting question then becomes not should I target, but how can I target effectively?

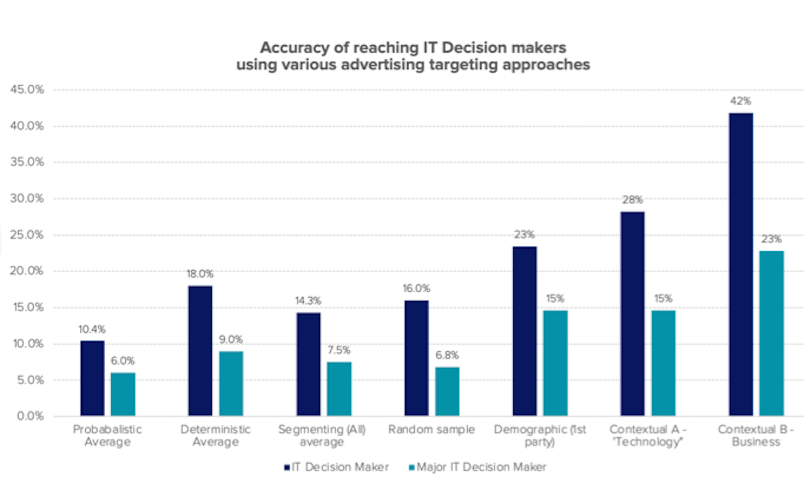

Neumann, Tucker, Subramanyam and Marshall’s recent paper just focuses its attention on whether data-driven digital targeting works to actually get you the audience you specified.

Spoiler alert, dear reader: the answer is no, it really does not. Surprise!

And there are much cheaper and simpler ways of trying to get to the right audience than using data to target bespoke audiences.

In this study, the researchers compared the use of different types of data-sets used to target media buying and looked at the accuracy of each, in terms of did they actually reach the specific audiences they were hoping to find? They looked at;

- “Probabilistic” data; using scraped online “third party” data,

- “Deterministic” data, i.e. second party data, when you directly buy email lists etc.,

- First party data. When you own and can verify the data and the database.

In summary:

What they found was any form of second or third-party data led segmenting and targeting of advertising does not outperform a random sample when it comes to accuracy of reaching the actual target.

Holy cookies Batman. Second and third party data does not outperform a random sample. Accuracy is well below 20 per cent. Let that sink in.

First party data does do better than the random sample. Thank God. You can all breathe a sigh of relief. And feel glad you have been building that first party data engine for the last three years. At least that’s not a waste of money.

But, and here’s the real kicker: Contextual ads massively outperform even first party data. And they are much, much cheaper.

“When further considering data costs, we find that content interest – which can be seen as a form of contextual targeting – appears to be not only the most effective, but also the most cost-efficient tactic.”

Holy database Robin.

Custom IT decision-maker segments are no more helpful for finding the desired audience than random prospecting from a digital publisher network.

We can improve the quality of our targeting much better by just buying ads that appear in the right context, than we can by using my massive first party database to drive the buy, and it’s way cheaper to do that. Putting ads in contextually relevant places beats any form of targeting to individual characteristics. Even using your own data.

Blimey. What. The. Actual. Fuck.

But it all connects nicely to Arielle Garcia's assertions and findings from last month. If the data that’s in the supply chain is shit, no surprise the results are shit.

WTF – this is all explosive and new right?

Maybe not so much. It’s far from the first time someone has said that contextual advertising is a good idea and that reach is important. It is, however, counter to a lot of current “data-driven” practice.

It is also entirely explainable and shouldn’t be a real surprise. It’s congruent with other things we know about how advertising works.

The secret to effective, immediate action-based advertising, is perhaps not so much about finding the right people with the right personas and serving them a tailored customised message. It’s to be in the right places. The places where they are already engaging with your category, and then use advertising to make buying easier from that place.

Advertising is a weak force. Even hard, sales-driving advertising isn’t the tough guy we want it to be. Advertising mostly works when it makes things easier, much more often than when it tries to persuade or invoke a reluctant action.

Thinking about advertising as an ease-making mechanism is much more likely to set us on the right path.

This is the weak force at work. But if you use it like this, it's also an awesome force. If you work with the weak force, it pays you back. Try to get it to toughen up and be more persuasive? The weak force just wilts under pressure.

If your ad is in the right place, you automatically get the right people, and you also get them at the right time; when they are actually more interested in what you have to sell. You also spend much less to be there than crunching all that data.

All you need to do now is just nudge them gently in the direction of whatever your shopping cart looks like by laying out the path to purchase for them like a red carpet.

Our belief that the right data will allow us to do better than that is potentially completely misguided. Even if we could get hold of some good data, which it seems is way harder than we might be led to believe by “big data”, we might still be better off with other simpler, cheaper tactics.

These are not the first studies to say that;

- the costs of targeting are high

- the costs of customising creative are also significant

- the data that is used is bad and hard to integrate

- that context is actually the smarter way to get the right people, in the right places, at the right time

- and it’s also by far the cheapest.

But it is good to see those ideas supported with peer-reviewed, statistically robust and evidence-based facts.

It’s possibly not an easy pill to swallow, especially if you have just spent $3 million building a massive martech stack. Or you are, for some reason, happy with the 36c on the dollar your programmatic buy delivers. Good job there’s room for some of that nuance here, then. There are perhaps good uses for those tools, it’s just that one of those uses might not be targeting the performance and programmatic-driven advertising buy.

While there are a lot of other nuances here, my observation is that we are not an industry currently engaged in much careful consideration of when data-driven, programmatically-targeted advertising might be a good and profitable idea. We have been leaping feet first into a data-driven hyper-targeted future. Perhaps we might want to think a little harder, and a little more carefully about that before we get very much further.

We might all be better served with a little more empirical circumspection around whether data driven media targeting is;

- the most cost-effective

- the best way to target people who would not have bought you anyway,

- whether any of the data we are using outperforms simpler mechanisms for finding the people we want to talk to

- whether the data that fuels the entire system is any good to begin with.

My suggestion, given the complexity that always surrounds these topics, is that you do your own experiments with your own curious and sceptical minds. If you can do that before you’ve blown millions of dollars on data and technology, you might end up looking a little less stupid at the end of it.

It might be a more interesting advertising world, certainly a cheaper one, with more money left in the budget for actual media, if we all went and tested some of these counter-trend ideas versus the “hyper personalisation is awesome, let’s go programmatic, martech – woo-hoo!” trend that seems to be the prevailing zeitgeist.

But what do I know? I am clearly stupid.

References:

Is first- or third-party audience data more effective for reaching the ‘right’ customers?

Nico Neumann Catherine E. Tucker Kumar Subramanyam John Marshall

Quantitative Marketing and Economics. July 2023.

Overwhelming targeting options: Selecting audience segments for online advertising.

Iman Ahmadi, Nadia Abou Nabout, Bernd Skiera, Elham Maleki, Johannes Fladenhofer

International Journal of Research in Marketing 2023.

Is it wise to prioritise #Reach over #Conversions?

Rikard Wiberg. Pace: Marketing Science, Analytics & Strategy. Stockholm. LinkedIn 2023