Edelman Trust Barometer shows Australians alarmed about AI, sceptical of innovation; fear cybersecurity and information wars more than inflation; trust peers and scientists more than CEOs and journos

The 24th edition of the Edelman Trust Barometer shows a 4 percentage point lift in trust sentiment across Australia, bringing us out of negative and into neutral territory. But underneath the topline figure is a bubbling pot of fear and scepticism, particularly with regards to new innovations such as AI and the way they’re being managed by government and business. Existential concerns prompted by technology – specifically cybersecurity and information wars – are also now superseding personal economic fears around inflation. This is despite the fact Australia’s wealth gap is playing a direct role in how we view and embrace innovation. For Edelman Australia CEO, Tom Robinson, increasingly politicised views plus the echo chamber of relying on peers and ‘people like me’ as trusted sources of information over and above government, business leaders, scientists and technical experts, is another worry. The message for brands and businesses? It’s time to reset thinking on business-government partnerships, spokespeople and messaging and turn up the dial on listening and nuance.

What you need to know:

- The 24th edition of the Edelman Trust Barometer shows a 4 percentage point lift in trust sentiment across Australia to 52, bringing us out of negative and into neutral territory. Yet we still continue to mistrust government and media.

- We also are a nation of sceptics when it comes to innovation and the rise of technologies such as AI, showing up as the secondhighest country after the US to believe innovation is being poorly managed.

- Australians are on par with China in believing the government lacks the competence to regulate emerging tech, and 59 per cent of us believe science has become politicised.

- Australia is additionally right up there in seeing society as changing too quickly and happening in ways that will not benefit ‘people like me’. The majority of Australians also believe technology is changing too quickly and in ways that are ‘not good for people like me’ and they fear government has too much influence over science.

- Politics and socioeconomic conditions both have a bearing on acceptance and trust of AI and innovation, with Edelman figures showing those on the right and those in lower income brackets are more likely to reject innovation over those on the left or with better economic circumstances

- We’re also at risk of an echo chamber given our reliance on community and people like us, says Edelman CEO Tom Robinson – though there is some hope, with scientists and technical experts much higher in standing when it comes to perceptions of truth tellers, over CEOs and government leaders.

Australia is showing itself to be a nation of sceptics when it comes to innovations such as AI and our faith in institutions to deliver them fairly, leading to outright rejection depending on our political views and socio-economic situation, Edelman’s latest Trust Barometer reveals.

In fact, our mistrust in technology has become so pronounced, we’re more fearful of existential threats such as cybersecurity and the information wars than we are inflation.

According to the 24th edition of the Edelman Trust Barometer, Australia’s overall trust scores are up 4 percentage points this year to 52, moving the nation into neutral sentiment territory. Government leaders, business leaders and journalists were all on par in terms of how much trust we place in what they tell us (59 per cent apiece, up 3, 5 and 2 percentage points, respectively).

This overarching figure masks discrepancy in trust depending on institutions and innovation, however. When asked who we trust when it comes to telling the truth around new innovations and technologies, ‘someone like me’ (73) was the top cohort for Australians, before scientists (71), company technical experts (58) and NGO representatives (54). Sources in negative territory include CEOs (40), government leaders (49) and the least trusted of the lot, journalists (38).

There are also clear differences depending on whether you’re in a higher or lower income bracket. For example, those on a lower income showed lower levels of trust across all four types of institutions (business, government, NGOs and media) compared to those on a higher income, averaging double-digit differences.

But where the real negativity becomes pronounced is when you start delving into the narrative around innovation and technology. Nearly all countries surveyed believed innovation is being mismanaged rather than well managed, with Australia (50) coming in as second place after the US (56). In Australia, 64 per cent believe the government lacks the competence to regulate emerging tech – a figure on par with China – and 59 per cent believe science has become politicised.

Australia was also found to be right up there in believing society was changing too quickly and happening in ways that will not benefit ‘people like me’ (73 per cent, versus a global average of 69 per cent). In addition, more Australians said technology is changing too quickly and in ways that are ‘not good for people like me’ (65 per cent against a global average of 60). More than half (55 per cent) believe the government has too much influence over science.

Then there are the stark differences in trust derived from different political leanings. In Australia, if you’re on the right, you’re much more likely to resist innovation (37 per cent) than someone on the left (14 per cent) – a 23-point difference.

A real resistance to innovation and AI

Speaking to Mi3 on the findings, Edelman CEO, Tom Robinson’s sum up view was we’re a sceptical bunch when it comes to the technology shift going on around us. Edelman’s report explored four areas of innovation in depth – AI, green energy, genetically modified (GMO) foods and gene-based medicine.

Green energy was the least rejected of innovations, with 44 per cent of Australian embracing it and only 16 per cent rejecting it. By contrast, 52 per cent of Australians rejected AI, against just 15 per cent embracing it. GMO food fared even worse, with 57 per cent rejection versus 10 per cent acceptance, while gene-based medicine was rejected by 25 per cent and embraced by 20 per cent of local respondents.

“By and large, we tend to view these innovations with that level of scepticism – particularly the role of AI, more so than most other APAC markets,” Robinson comments. “When it comes to AI, there’s a real tendency in Australia to reject the innovation outright and resist that change. By and large, that comes down to the unknown – it’s the feeling we’re not being communicated to clearly and we don’t know the tangible benefits of that innovation. There’s an underlying fear around the role business and government are taking in applying that innovation as well.

“For marketers and anyone within the communications space, it’s incumbent to firstly listen, but also to think about how we are implementing. In many ways, the approach is more important than the innovation itself. That’s where we’re seeing a failure by and large.”

Robinson admits it’s a paradox at play in society that’s particularly pronounced in Australia. “Innovation and the role of AI is supposed to usher in a new era of economic prosperity as we move away from this cost-of-living crisis. On the other hand, there’s real fear, both personal and more existential, around the role it will play in exposing me to risk,” he says.

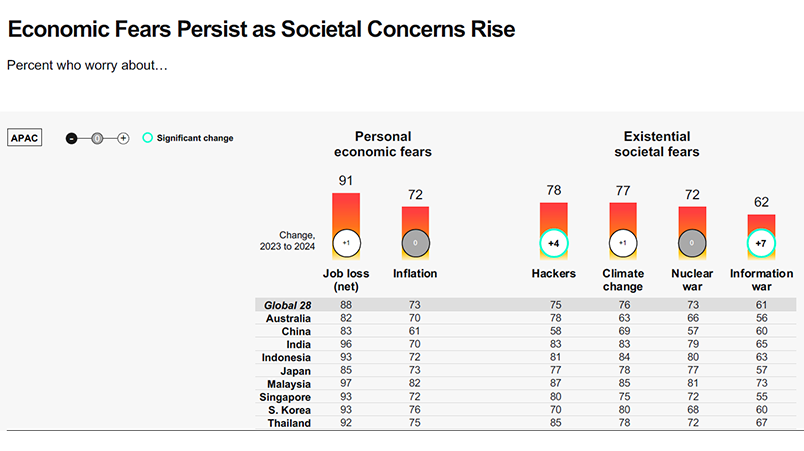

Within the list of existential, societal fears, two new additions to Edelman’s top four in Australia are cybersecurity – specifically, hackers – and the information war. Job loss is the top fear for Australians. But hackers are even more frightening than inflation.

“Everyone would think all that dominates is cost-of-living, housing, economy and inflation. But actually, cybersecurity and threat of hackers is a greater fear than inflation itself,” Robinson says. “We have shifted away from real concern around energy and food shortages, which we experienced in the last couple of years across the supply chain, to the role of technology and innovation not just offering us a better future, but actually keeping us safe.”

When it comes to AI, there’s a real tendency in Australia to reject the innovation outright and resist that change. By and large, that comes down to the unknown – it’s the feeling we’re not being communicated to clearly and we don’t know the tangible benefits of that innovation. There’s an underlying fear around the role business and government are taking in applying that innovation as well.

Politics, socio-economic circumstances divide views

For Robinson, such fears are amplified by negative narratives seen in the media and some institutions, which create more tension and mistrust. They’re also influenced by Australia being on the cusp of polarisation – something Edelman highlighted in its 2023 report.

“That division very much plays a part in this. And that’s where the Covid hangover is – division in terms of generational divide, political divide, and division in terms of the wealth gap,” he says.

Robinson points to that gap between left and right views on innovation to prove the point. “That 23-point gap is the second highest globally we tracked outside the US when it comes to innovation. Those ideologies shape our identity in many ways,” he says. “That also influences our trust and faith in the future. There’s that sense those who potentially sit on the political right, or who are not benefitted economically in the last few years, feel like they’re being left behind.”

Bringing that back to the role of business, marketing and communications, Robinson stresses the need for better understanding and an “awakening that society is not homogenous”.

“We have to understand these differences if and when we’re expecting people to lean into organisation or behavioural change on behalf of business,” he says. “That exists just as significantly among employees as it does your customers.

“Regardless of whether it’s a political, societal or economic debate, ensuring these different voices are heard and you’re thinking about that in terms of application to organisation, business change and transformation is quite key. By and large, what we’re seeing in this report is that this isn’t happening.”

It’s also worth rethinking your spokespeople. Commonly, the advice has been to look to business leaders and the CEO as the authorial voice.

“What this report is telling us this year is it might not be the best voice,” Robinson says. “Who people want to hear more from are the scientists and technical experts in the field – they were the top two of five voices [77 per cent and 74 per cent respectively in Australia; 75 per cent and 73 per cent globally]. People want them to be leading implementation of innovation. Then it’s followed by academics and government leaders. But it's quite interesting – business leaders and CEOs are not featured in the top five of people audiences want to hear from around these innovations.”

There’s another nugget here in terms of innovation and partnerships, implementation strategy and representation. Based on Edelman’s report, Robinson says it’s clear business and government working together in partnership can do a lot more together than alone. Figures show demand for business-government partnership on innovation has lifted 19 points in the last decade to 55 per cent compared with 70 per cent in APAC and 60 per cent globally.

“There is a real tension point now, looking at the science and everything going into bringing innovations to market – they have become too politicised. Those involved in funding have too much influence on how it is all done. Business probably needs to step up there and be seen to be taking greater ownership and working with government on solutions,” Robinson says.

There is a job for our big tech companies to do to ensure diversity of thought and opinion is coming through. That would offset some of the macro shifts we are seeing from establishment leaders to local communities. The real challenge now is this battle for truth, which is ongoing – who, where and what should I trust. Right now, people feel they’re not hearing the whole truth.

Contradictory views on institutions and trusted sources

In terms of the most used sources of information for new technologies and innovations, national media leads in Australia (51), followed by online searches (43), friends and family (40), local media (37) and social media (35). This was different to APAC results, where social media topped the list.

“National media still plays a role, as does social, yet the trust in media is still low – it’s our least trusted of the institutions locally and globally [47 in APAC versus 65 in business, 62 in gov and 59 in NGOs],” Robinson comments.

How consumers more broadly view institutions and their competence is shifting too, Robinson says, adding to the list of contradictions around innovation and trust. Take energy, where there’s real acceptance of the benefits of green energy.

“Yet as a sector, energy sits in neutral territory and of the four we studied, was the least trusted sector,” Robinson says. “With food and beverage, which has overall strong trust scores that don’t change much year-on-year, the gap in trust in innovation of GMO foods is significant. There’s a real pushback and rejection of genetically modified foods, but trust in the sector to do what’s right.”

The pace of change is at work here, Robinson agrees. “When speed of change is happening too quickly, pushback happens,” he says. But divisions in society – both generational as well as the wealth gap – are equally real and reflected in how much consumers will lean into change.

“Those not feeling they’re being brought on the journey, feel they’re being left behind or not benefitting in our current economic circumstances, which is by and large those impacted by the cost-of-living crisis, will lean back and reject that pace of change,” he says. “That’s the challenge for business, marketers and anyone in the comms industry: How do you navigate that? At a time when these new technologies are hitting the markets with speed… we have these challenges where when they are being brought to market, there’s a quick pushback narrative and it’s from those same people who are being caught out there.

The longer narrative Robinson says Edelman’s barometer points to is Australian consumers not placing as much trust in traditional leaders as we once did and favouring community instead.

“We look to people ‘like me’ – people with similar beliefs, circumstances, and place trust in those. In addition, the shift we’ve seen this year is technical experts and scientists are coming to the fore a bit more,” he says. “The challenge we have there is they don’t have a strong enough voice. Because if we lean too much into my local community, friends and family, we go down the rabbit hole – the ‘echo chamber’. If you’re using social media or search as your primary source of trusted information, the role of the algorithms will make sure of that. There is a job for our big tech companies to do to ensure diversity of thought and opinion is coming through. That would offset some of the macro shifts we are seeing from establishment leaders to local communities.

“The real challenge now is this battle for truth, which is ongoing – who, where and what should I trust. Right now, people feel they’re not hearing the whole truth.”

This year’s Edelman Trust Barometer includes more than 1,100 responses from consumers in each of the 28 countries surveyed including Australia.